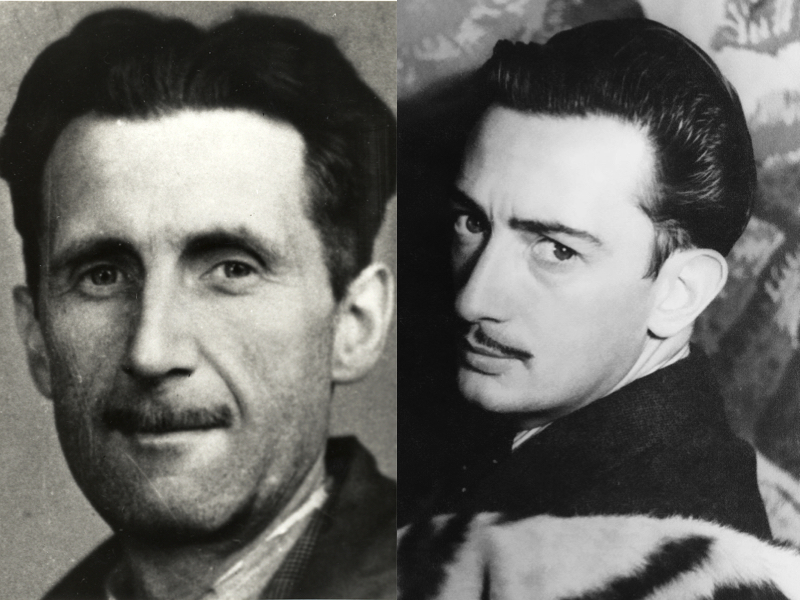

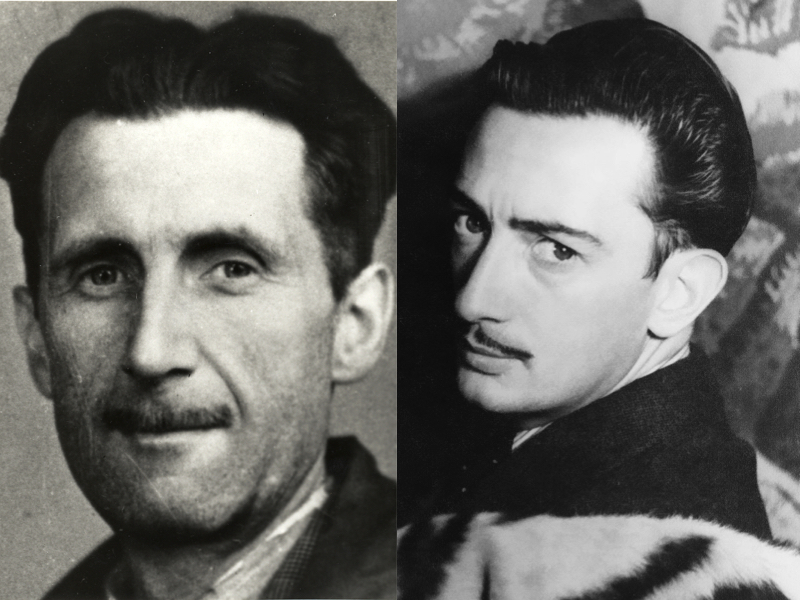

Images or Orwell and Dali via Wikimedia Commons

Should we hold artists to the same standards of human decency that we expect of everyone else? Should talented people be exempt from ordinary morality? Should artists of questionable character have their work consigned to the trash along with their personal reputations? These questions, for all their timeliness in the present, seemed no less thorny and compelling 81 years ago when George Orwell confronted the strange case of Salvador Dali, an undeniably extraordinary talent, and—Orwell writes in his 1944 essay “Benefit of Clergy”—a “disgusting human being.”

The judgment may seem overly harsh except that any honest person would say the same given the episodes Dali describes in his autobiography, which Orwell finds utterly revolting. “If it were possible for a book to give a physical stink off its pages,” he writes, “this one would.” The episodes he refers to include, at six years old, Dali kicking his three-year-old sister in the head, “as though it had been a ball,” the artist writes, then running away “with a ‘delirious joy’ induced by this savage act.” They include throwing a boy from a suspension bridge, and, at 29 years old, trampling a young girl “until they had to tear her, bleeding, out of my reach.” And many more such violent and disturbing descriptions.

Dali’s litany of cruelty to humans and animals constitutes what we expect in the early life of serial killers rather than famous artists. Surely he is putting his readers on, wildly exaggerating for the sake of shock value, like the Marquis de Sade’s autobiographical fantasies. Orwell allows as much. Yet which of the stories are true, he writes, “and which are imaginary hardly matters: the point is that this is the kind of thing that Dali would have liked to do.” Moreover, Orwell is as repulsed by Dali’s work as he is by the artist’s character, informed as it is by misogyny, a confessed necrophilia and an obsession with excrement and rotting corpses.

But against this has to be set the fact that Dali is a draughtsman of very exceptional gifts. He is also, to judge by the minuteness and the sureness of his drawings, a very hard worker. He is an exhibitionist and a careerist, but he is not a fraud. He has fifty times more talent than most of the people who would denounce his morals and jeer at his paintings. And these two sets of facts, taken together, raise a question which for lack of any basis of agreement seldom gets a real discussion.

Orwell is unwilling to dismiss the value of Dali’s art, and distances himself from those who would do so on moralistic grounds. “Such people,” he writes, are “unable to admit that what is morally degraded can be aesthetically right,” a “dangerous” position adopted not only by conservatives and religious zealots but by fascists and authoritarians who burn books and lead campaigns against “degenerate” art. “Their impulse is not only to crush every new talent as it appears, but to castrate the past as well.” (“Witness,” he notes, the outcry in America “against Joyce, Proust and Lawrence.”) “In an age like our own,” writes Orwell, in a particularly jarring sentence, “when the artist is an exceptional person, he must be allowed a certain amount of irresponsibility, just as a pregnant woman is.”

At the very same time, Orwell argues, to ignore or excuse Dali’s amorality is itself grossly irresponsible and totally inexcusable. Orwell’s is an “understandable” response, writes Jonathan Jones at The Guardian, given that he had fought fascism in Spain and had seen the horror of war, and that Dali, in 1944, “was already flirting with pro-Franco views.” But to fully illustrate his point, Orwell imagines a scenario with a much less controversial figure than Dali: “If Shakespeare returned to the earth to-morrow, and if it were found that his favourite recreation was raping little girls in railway carriages, we should not tell him to go ahead with it on the ground that he might write another King Lear.”

Draw your own parallels to more contemporary figures whose criminal, predatory, or violently abusive acts have been ignored for decades for the sake of their art, or whose work has been tossed out with the toxic bathwater of their behavior. Orwell seeks what he calls a “middle position” between moral condemnation and aesthetic license—a “fascinating and laudable” critical threading of the needle, Jones writes, that avoids the extremes of “conservative philistines who condemn the avant garde, and its promoters who indulge everything that someone like Dali does and refuse to see it in a moral or political context.”

This ethical critique, writes Charlie Finch at Artnet, attacks the assumption in the art world that an appreciation of artists with Dali’s peculiar tastes “is automatically enlightened, progressive.” Such an attitude extends from the artists themselves to the society that nurtures them, and that “allows us to welcome diamond-mine owners who fund biennales, Gazprom billionaires who purchase diamond skulls, and real-estate moguls who dominate temples of modernism.” Again, you may draw your own comparisons.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2018.

Related Content:

When The Surrealists Expelled Salvador Dalí for “the Glorification of Hitlerian Fascism” (1934)

George Orwell Reviews Mein Kampf: “He Envisages a Horrible Brainless Empire” (1940)

How the Nazis Waged War on Modern Art: Inside the “Degenerate Art” Exhibition of 1937

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness